Many figures once regarded as “opposition,” such as Abdolkarim Soroush, were themselves architects of the “Cultural Revolution,” while others, like Mir-Hossein Mousavi (who, despite holding only a master’s degree in architecture, evaluated Ph.D. theses in political science) and his wife, were among its beneficiaries. The “Cultural Revolution” was, without doubt, and rightly so, the second revolution of the 1979 revolutionaries to solidify their propaganda apparatus. It provided a framework that allowed the regime’s totalitarianism to distribute cultural capital as patronage among its supporters.

The role of quotas and selection processes in controlling and managing the composition of students and faculty was unparalleled. The manufacturing of personas occurred systematically and with great force. There was little difference between conservatives, reformists, and so-called “transformation-seekers” (those excluded from political power but still part of the permissible social hierarchy). Even individuals like Hossein Allahkaram could be granted a Ph.D. and a university professorship under this system. The magnitude of this disaster went far beyond mere discrimination or an attack on meritocracy.

Pierre Bourdieu, the French sociologist, distinguishes between three types of capital—economic, social, and cultural—that are interconvertible. The famous term “cultural middle class” also originates from Bourdieu’s perspective, as, like economic capital, social and cultural capital are distributed in various forms across different social classes. With this understanding, the role of the “Cultural Revolution” as the beating heart of a totalitarian regime’s propaganda machine becomes clearer.

In Iran, university degrees, particularly beyond the undergraduate level, are often distributed as cultural rent within society. Academic positions, such as university faculty memberships, serve as cultural patronage granted to loyalists. Occasionally, various governmental factions have sought to establish or expand their affiliated universities (e.g., Hashemi Rafsanjani’s Azad University or Ahmadinejad’s Payame Noor University). Members of parliament, governors, mayors, and many individuals presented in pro- and anti-regime media as analysts have all passed through the Islamic Republic’s system of cultural rent distribution. They knowingly or unknowingly, consciously or unconsciously, propagate the regime’s propaganda, leveraging other controlled institutions, such as media, for this purpose.

The university is but one example of many institutions marred by control and dysfunction. However, it holds a central role in producing propaganda. A vast amount of pseudo-science is generated under the guise of science and promoted as ideological advertisement.

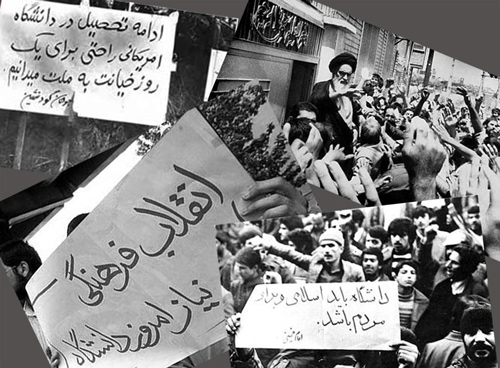

Cultural revolutions occurred in both Iran and China. In Iran, following the Cultural Revolution, course content, elective units, thesis evaluations, research assessments, and the management of academic journals were all determined under the oversight of the Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution. Although the stated objectives of the Council appeared to be the promotion of Islamic culture, the purification of academic environments from materialistic ideologies, and the rejection of Westernization, its hidden agenda was to control cultural capital and exploit it unilaterally for the regime’s benefit. Similarly, in China, although Mao claimed the Cultural Revolution aimed to combat old customs and traditions, in practice, it resulted in a “Great Purge,” concentrating cultural rent within the Communist Party’s propaganda machinery.

The example of academic rent is merely illustrative of a broader picture. The massive distribution of cultural capital as rent within universities, think tanks, and media has skewed them toward preserving the status quo. As a result, the output of the current defective system should be considered largely irrelevant. To draw a figurative comparison, in debates over the Syrian revolution, a political science professor at the University of Tehran is wrong 90% of the time compared to a taxi driver.

The transformations within Iranian society and the rise of nationalist discourse have significantly undermined the authority of mainstream media and the intellectuals of the 1979 revolutionaries. This shift has created an opportunity for Iran’s national opposition to frame issues through the lens of national interests, paving the way for transitioning from the Islamic Republic to restoring a national government.

The Think Tank of Iranian Affairs is also an attempt to produce content relevant to Iran’s contemporary conditions and regional developments, aiming to expand theoretical foundations and explore the challenges of reviving a modern state in Iran.