By: Mehdi Ghadimi

A year ago, around this time, the premature yet hidden excitement of some individuals and groups following the terrorist crimes of October 7th prevented them from believing the opening of Pandora’s box. It goes without saying that these individuals and groups belong to various factions that, for the past 45 years, have either denied or remained oblivious to the opening of the original Pandora’s box in February 1979. This denial stems from either being among those who opened the box or having benefited politically and economically from its opening.

These groups and individuals, continually avoiding confrontation with reality, still refuse to acknowledge that the Islamic Republic has reached a point of no return. Its survival is now more inversely related to the salvation of Iran than ever before. At times, they reduce the idea of moving beyond the Islamic Republic to “selling dreams”; other times, they instill public fear of change by warning of a “Syrian scenario” for Iran. Sometimes, they attempt to discredit the movement for transitioning from the Islamic Republic and its leader, Prince Reza Pahlavi, by targeting him. It is evident that what emerges from this confluence of ideas in the womb of Iranian politics is nothing but the embryo of “reformability of the Islamic Republic” or “systemic transformation from within,” conceived from many fathers, none of whom will take responsibility for this creation.

Nevertheless, if we step outside the noisy yet ineffective circle of these currents and try to think about Iran in the real world, describing Iran’s current state and future possibilities requires confronting harsh realities and preparing for difficult decisions and their consequences. The complexity of the current situation and the sensitivity of upcoming decisions are so significant that some individuals and groups, fearing the challenges, have perhaps knowingly decided to close their eyes to reality and engage in a delusional fight against windmills. Thus, their platforms and movements continue to thrive in the media.

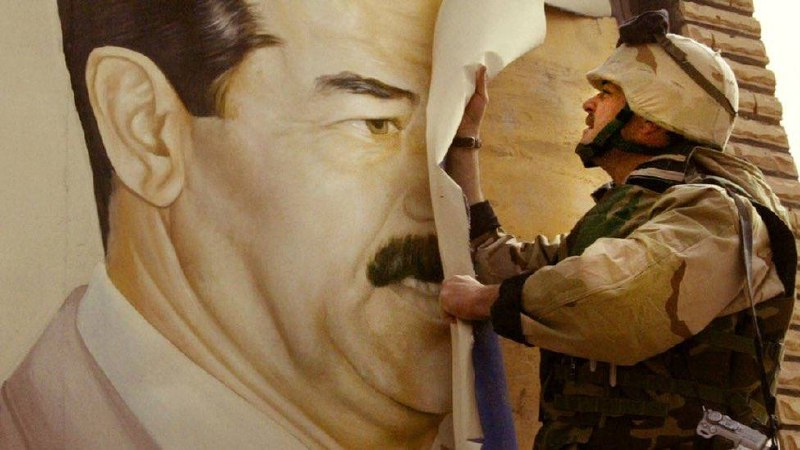

To grasp the real picture of Iran today, it is essential to examine the status of regimes similar to the Islamic Republic in the years leading to their downfall. This examination can provide a clearer understanding of the trajectory taken and the possible outcomes ahead. For this purpose, we can look at notable contemporary examples of regime change, such as Poland, the Czech Republic, Yugoslavia, Allende’s Chile, Saddam’s Iraq, and Gaddafi’s Libya, to gain a rough estimate of the path the Islamic Republic has set for Iran.

It is important to clarify that the revolutions in Egypt and Tunisia are not considered comparable examples in this analysis. The foundational conditions of those revolutions differ fundamentally from the current situation of the Islamic Republic. The regimes in those countries did not present themselves as a significant threat to the global order, nor did they actively engage in enmity with certain nations. They had not positioned themselves as one side of a global power struggle or become perceived threats to other countries. In contrast, the governments considered in this analysis—ideological regimes at odds with their neighbors or parts of the international community—insisted on exacerbating these conflicts and aligning with ideological blocs.

If we compile a list of the most critical problems faced by these regimes during the final decade of their existence, we will observe the following:

Economic Crises

– The spread of poverty, unemployment, and a deep class divide, along with widespread inequality among the people

– Severe inflation

– A decline in production, especially in key industries on which the national economy is heavily dependent

– Rising public expenses, a drop in the value of the national currency, a significant decrease in purchasing power, and a noticeable decline in the standard of living for ordinary citizens

– Governmental inability to cover increasing expenses and mounting public debt

Political Crises

– Intense internal conflicts among factions with shared vested interests in the government

– Worsening financial and administrative corruption, alongside systemic inefficiency at various intermediate and high levels of governance

– Escalating violence and repression

– Uprisings, strikes, opposition demonstrations, and the occurrence of political assassinations

International Crises

– Economic sanctions and growing international isolation

– Withdrawal of foreign supporters due to international pressures or evolving regional and global conditions

If there is only one issue from the above list that has yet to fully manifest concerning the Islamic Republic, it is the final point: the abandonment of support from both overt and covert allies of the regime. Nearly all other examples accelerated their collapse and regime change, often facilitated or directly intervened in by Western powers, following a decline in Moscow’s ability to sustain them. However, this external support, while a necessary condition, also required a substantial level of persuasion among these powers to act.

For instance, if Saddam Hussein had cultivated a “reformist” faction within his regime that successfully lobbied the U.S. and European governments, convincing them that the Iraqi regime was capable of reform and negotiation, the decision to undertake military action against Iraq, and achieving bipartisan consensus in the U.S., might not have been as easily available to George Bush.

From this perspective, when assessing the current state of the Islamic Republic, one might see the diminishing Russian support—due to Moscow’s preoccupation with the war in Ukraine—as a weakening pillar of external backing for the regime. Additionally, the discrediting of the so-called reformist faction both domestically and internationally could be considered a second eroding base of support. Yet, all evidence suggests that the Islamic Republic has not completely lost either of these bases. Instead, it appears that, under present conditions, it must offer more concessions to maintain this external support. (This is precisely why the survival and continuation of the Islamic Republic are now more inversely related to Iran’s existence and the preservation of our territorial integrity than ever before.)

Considering all these factors, we are confronted with the main challenge: answering the most crucial question facing the people and the opposition of the Islamic Republic. The question is: given all these conditions, what strategies and options do we have for transitioning from the Islamic Republic and saving Iran?

To address this question, we can refer to the examples mentioned above and categorize the paths taken in these countries into three main approaches:

First, countries where international pressure and sanctions, combined with diminishing support from foreign allies, forced the ruling government to negotiate with the opposition and peacefully transfer power. Poland and the Czech Republic are examples of this category.

Second, countries where internal political and economic collapse led to a military coup. In this category, one can examine not only Chile’s experience but also that of Spain in a more distant past.

Third, countries that refused to change their behavior despite international pressure, ultimately leading to a consensus for military intervention. Yugoslavia, Iraq, and Libya fall into this category.

In Iran’s current situation, the likelihood of a scenario like the first category occurring—where the regime steps down, agrees to a referendum, and allows the return of a figure like Prince Reza Pahlavi as the leader of the opposition for a peaceful transition—is almost nonexistent. Additionally, there is little indication that the country will reach a level of internal conflict where the central government loses control over systemic disputes and social disorder, and military factions with different approaches from the ruling establishment manage to stage a coup and restore order. Given the weakened decision-making structure of Iran’s army under the Islamic Republic and the economic and military dominance of the Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), it is unrealistic to expect the army to play such a role, and a coup by the IRGC would only be conceivable in a scenario similar to the Soviet collapse and the reformation of the KGB.

In the third category, the core issues that Yugoslavia faced, mainly due to its multiethnic nature, are not directly comparable to Iran’s situation. However, the ideological and behavioral similarities between the Islamic Republic and the regimes of Saddam Hussein and Muammar Gaddafi—so strikingly similar that they sometimes seem intentionally replicated—make a scenario akin to these two countries more plausible.

It is essential to highlight that the preferences of the Islamic Republic’s opponents, whether among the general population or various political groups, hold little practical guarantee or decisive influence over future events. While everyone might ideologically prefer a peaceful transition through the voluntary resignation of current rulers or a revolution similar to Tunisia’s, the reality of what will shape future events lies in the regime’s actions and the responses of powers influenced by these actions.

What is currently analyzable is that the strategic precision in the recent Israeli airstrikes and the lack of condemnation from Western powers, and even from China and Russia, signal a shift towards military action. This, combined with the extensive similarities between Saddam Hussein’s regime and the Islamic Republic—ranging from both regimes’ reliance on Moscow to their shared claims of leading the Islamic world against Israel and fighting imperialism while opposing U.S. presence in the region—positions Iraq under Saddam as the closest comparable scenario. The Islamic Republic’s missile launches toward Israel even resemble Saddam’s symbolic attacks on Tel Aviv and Haifa. Although these Iraqi missile attacks marked the beginning of the countdown to Saddam’s downfall, his regime ultimately fell 12 years later.

If we view Iran’s current position in the global order as similar to Iraq after the invasion of Kuwait, Prince Reza Pahlavi’s remarks about the necessity of choosing a different path by global powers become clearer. From the day the world decided it would no longer tolerate Saddam’s behavior to the eventual military intervention aimed at ending his rule, only two options were considered viable: sanctions aimed at changing behavior or military intervention to topple the regime. If today’s global powers adopt the same view towards Iran, they may resort to military action as soon as they lose hope in altering the Islamic Republic’s behavior.

What needs to be carefully considered is that the concept of changing the behavior of the Islamic Republic can encompass many aspects. However, what has been explicitly and publicly articulated was outlined by Mike Pompeo, the Secretary of State under Donald Trump, as the preconditions for any negotiations with the Islamic Republic. It is reasonable to estimate that, with some modifications, the overall expectations for behavior change from the global powers remain close to these conditions. The 12 points are as follows:

1- Iran must provide the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) with a full account of the prior military dimensions of its nuclear program.

2- Iran must stop all uranium enrichment and never pursue plutonium reprocessing; this includes closing its heavy-water reactor.

3- Iran must allow unqualified access to all sites throughout the entire country for IAEA inspectors.

4- The development of Iran’s ballistic missile program must cease, and Iran must not conduct any launches of missiles capable of carrying nuclear warheads.

5- All U.S. citizens, as well as citizens of our allies detained on false charges, must be released.

6- Iran must end its support for terrorist groups in the Middle East, including Hezbollah, Hamas, and the Palestinian Islamic Jihad.

7- Iran must respect the sovereignty of the Iraqi government and permit the disarming, demobilization, and reintegration of Shia militias.

8- Iran must end its military support for the Houthi militia in Yemen and work toward a peaceful political settlement.

9- All Iranian forces under the command of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) must withdraw from Syria.

10- Iran must stop supporting the Taliban and other terrorist groups in Afghanistan and the region and cease harboring senior al-Qaeda leaders.

11- The IRGC’s Quds Force must end its support for terrorism and militant proxies worldwide.

12- Iran must cease threatening behavior against its neighbors, many of whom are U.S. allies, including threats to annihilate Israel and missile attacks on Saudi Arabia and the UAE, as well as threats to international shipping and cyberattacks.

From a broader perspective, it appears that some of these demands, which the Islamic Republic has never willingly accepted, have been enforced over the past year. The most significant of these is Iran’s support for Hamas and Hezbollah, with the regime now almost entirely unable to continue such support. These examples send a clear signal to the world that changing the behavior of the Islamic Republic is only achievable through force. If the international community were to rely on the hope of behavioral change, as it did with Saddam Hussein in his final years, every passing day would bring greater harm to Iran’s environment, economy, infrastructure, and territorial integrity on one side, and to regional and global security and stability on the other. If the option of a behavioral change for the Islamic Republic is taken off the table, then for foreign powers, the only remaining alternative is military action.

At this critical juncture, Prince Reza Pahlavi advocates for supporting the national revolution of the Iranian people and placing trust in the national leadership and an expert body ready to govern during the transitional period. The question remains: What practical possibilities exist within the country, and what level of international support can this solution realistically receive? This is the most crucial consideration for any individual or group genuinely concerned for Iran, and they must take every possible step toward achieving it.

These efforts must be made with the understanding that the post-regime change order is a key factor for global decision-makers. At this moment, regardless of ideological, political, economic, or partisan perspectives, the only option that can assure these powers of a stable democratic transition in Iran, based on its own social foundations, is Prince Reza Pahlavi. Dismissing this option in any form is effectively accelerating the Islamic Republic’s push to draw Iran into a warzone. This reality holds true regardless of whether these accelerators are supporters of the “Axis of Resistance” or opponents who still cling to the revolutionary ideals of 1979, or even those who, despite abandoning those ideals, remain intent on removing the option of saving Iran simply because of sensitivity to the Pahlavi name.

The even harsher reality that every patriot must consider is the serious possibility of a military intervention being put on the agenda. For foreign powers and some groups opposed to the Islamic Republic, this remains the most likely scenario. There are still individuals and factions focused on undermining national leadership instead of taking steps toward a national revolution. As a result, national forces must be prepared to play their historic role if such an event occurs. This means that placing all hopes solely on a national revolutionary movement could prevent these forces from considering emergency measures should the likelihood of military action increase. If such an event transpires, having a cohesive and prepared national force, with a credible leadership, will ensure that Iran does not need to rely on foreign intermediaries to manage the transition, nor will it fall prey to the provocations of certain countries seeking to spark internal conflicts based on ethnic or religious divisions.